Клинический разбор в общей медицине №8 2025

Mutah University, Al-Karak, Jordan

Kabdelsater@mutah.edu.jo

Abstract

Background. The biggest risk factor for Alzheimer's disease (AD) is aging, contributing to impaired clearance of tau and amyloid-beta proteins, microglial senescence, endoplasmic reticulum stress, lipid dysregulation, and excitotoxicity.

Objective. This review investigates how aging speeds up the pathophysiology of AD and evaluates emerging geroscience-based interventions targeting biological aging mechanisms to delay or prevent cognitive decline.

Methods. A narrative review of the literature from 2015 to 2025 was conducted, integrating longitudinal studies, meta-analyses, and preclinical models that examine the aging-AD interface. The MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane, Google Scholar, and PubMed databases were searched using specifically related keywords, such as ageing, AD, AD pathology, anti-aging strategies, and AD therapies.

Results. From the initial search, more than 150 studies were excluded, and only 100 studies were selected for this review. After revision also duplicated 30 studies were removed. Ultimately, the review comprised seventy studies. Most of these studies discussed aging-related mechanisms – glymphatic dysfunction, APOE ε4-associated lipid transport impairment, BDNF depletion, and glutamate excitotoxicity, and anti-ageing strategies such as lifestyle interventions (e.g., physical activity, sleep optimization, cognitive engagement) and medical and biological therapies for AD.

Conclusion. Targeting aging mechanisms offers a paradigm shift in AD prevention and treatment; however, multidisciplinary collaboration is essential to translate geroscience into clinical practice. The integration of lifestyle and pharmacological strategies may yield synergistic neuroprotective benefits. Future research should focus on integrated, multimodal interventions that combine lifestyle modification with pharmacological and biological therapies. Tailored approaches–based on genetic risk profiles (e.g., APOE status), comorbidities, and individual aging trajectories–may optimize clinical outcomes. To evaluate the long-term safety and effectiveness of innovative treatments like senolytics, epigenetic modulators, and stem cell-based therapies in older populations, extensive, longitudinal clinical trials are also required. Developments in biological age biomarkers, machine learning, and systems biology have the potential to improve risk assessment and therapy customization.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, aging, neuroinflammation, senolytics, epigenetics, stem cell therapy.

For citation: Abdel-Sater K.A. Geroscience-guided approaches for Alzheimer’s disease: targeting aging mechanisms for therapeutic intervention. Clinical review for general practice. 2025; 6 (8): 22–30 (In Russ.). DOI: 10.47407/kr2025.6.8.00654

Introduction

Between 60% and 80% of dementia cases worldwide are caused by Alzheimer's disease (AD), making it the most prevalent type of dementia [1]. As of 2025, approximately 60 million people worldwide are affected by dementia, and by 2050, projections suggest a rise to nearly 210 million 2050 [2]. Age is the strongest risk factor, with AD affecting nearly half of those aged >85 years [3]. In both the United States and Europe, the prevalence of AD increases with age, from 0.85% among individuals aged 65–69 years to 44.35% in those aged over 95 years [4].

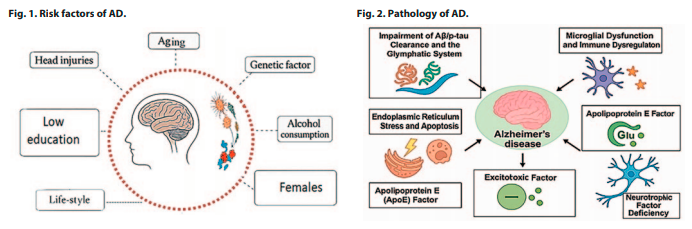

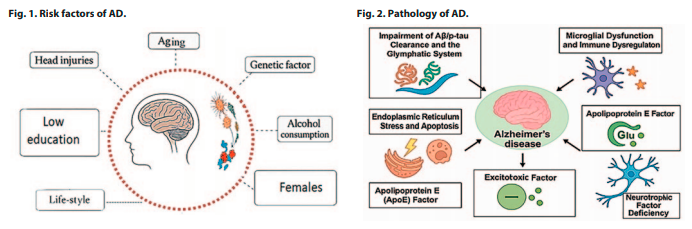

In addition to aging, Fig. 1 shows several other factors that contribute to AD risk, including female sex, genetic predisposition, low educational attainment, head injuries, and lifestyle-related behaviors such as a sedentary lifestyle, smoking, alcohol use, and obesity. These risk factors synergistically interact with aging to promote the development of AD [5].

Despite years of research, the treatment of AD remains limited. This highlights the need for novel approaches that target the underlying pathophysiology. The biggest risk factor for AD is aging, and targeting aging processes may be more successful than Aβ/p-tau strategies in altering the course of AD. This review critically evaluates the biological pathways through which aging contributes to AD pathogenesis and examines innovative lifestyle and pharmacological interventions that target these processes.

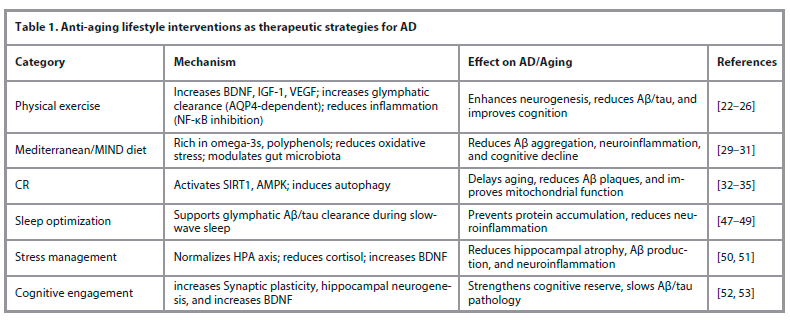

AD pathology: possible role of ageing

Aging induces systemic biological changes that disrupt homeostasis at the molecular, cellular, and tissue levels. These alterations include mitochondrial dysfunction, impaired proteostasis, genomic instability, oxidative stress, inflammation, and reduced regenerative capacity. In the brain, aging disrupts proteostasis, synaptic function, immune surveillance, metabolism, and the blood-brain barrier's (BBB) integrity [3]. The formation and clearance of amyloid-beta (Aβ) and phosphorylated tau (p-tau), neurotransmitter synthesis and release, microglial and astrocyte responses, neuronal excitability and plasticity, gut microbiota functions, and autophagy are all rapidly disrupted by these age-related changes – including oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and BBB breakdown–disrupt protein clearance, synaptic function, and immune regulation, ultimately driving AD progression (Fig. 2) [4].

1. Impairment of the Aβ/p-tau clearance and the glymphatic system

Aβ A is an acquired biomarker that can be used to predict disease because it appears a long time before the clinical signs of AD [6]. Under normal physiological conditions, Aβ is produced by neurons and efficiently removed via the glymphatic flow during sleep [7]. At normal levels, Aβ has numerous vital functions, including neuroprotection, memory improvement, and neuronal growth and repair. The accumulation of Aβ plaques is due to an imbalance between production and clearance. Its accumulation activates immune responses, causing neuronal destruction and memory impairment [6]. p-tau interacts with Aβ, exacerbating neurodegeneration through processes such as hyperphosphorylation [7].

With advancing age, several structural and functional changes compromise the glymphatic efficiency. These include reduced aquaporin-4 (AQP4) polarization, diminished arterial pulsatility, and impaired cerebrospinal fluid and interstitial fluid exchange. Consequently, aged brains exhibit reduced clearance of Aβ, facilitating its aggregation into extracellular plaques, which is a defining feature of early AD pathology [8].

Experimental evidence from aged rodent models and human neuroimaging studies has demonstrated a significant decline in glymphatic clearance, which correlates with an increased Aβ burden. Interventions that improve sleep architecture, enhance vascular function, or stimulate AQP4 expression are being explored as therapeutic strategies to restore the glymphatic function and slow AD progression [6].

2. Microglial dysfunction and immune dysregulation in aging

The brain's macrophages, known as microglia, are essential for preserving the homeostasis of the central nervous system because they monitor the surroundings, control inflammatory reactions, remove debris, including Aβ, and promote synaptic plasticity [9].

However, with aging, microglia undergo functional decline, shifting from a neuroprotective to a pro-inflammatory state due to transcriptional changes that upregulate inflammatory genes while downregulating homeostatic genes [10]. This dysfunction is exacerbated by reduced phagocytic efficiency, which impairs the clearance of Aβ and contributes to plaque accumulation, neurotoxicity, and tau pathology [8].

At the same time, pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1 (IL-1β), IL-6, tumor necrosis factor-α, and -γ are elevated due to systemic immunological dysregulation in aging, which impairs memory formation, synaptic integrity, and neuronal function [11]. Central to this process is the transcription factor nuclear factor κB (NF-κB), which is activated by oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and cellular senescence, which perpetuates inflammatory signaling. Together, microglial dysfunction and immune dysregulation create a vicious cycle of chronic inflammation and neuronal damage, accelerating age-related cognitive decline [12]. Therapeutic approaches aimed at reducing microglial senescence, including senolytic therapy, may reduce neuroinflammation and restore microglial homeostasis, offering a promising avenue for age-related AD therapy.

3. Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and apoptosis

The ER is crucial for protein folding, calcium homeostasis, and lipid synthesis. Under normal conditions, the ER maintains proteostasis via a tightly regulated quality control system. With aging, protein misfolding and metabolic stress increase, neurofibrillary tangles destabilize microtubules, and induce p-tau. Aβ is also produced through the overexpression of beta-site amyloid precursor protein-cleaving enzyme 1 [13].

A distinct initial imbalance or shock of aberrant proteins triggers apoptosis by activating caspases via extrinsic and intrinsic (mitochondrial) pathways, which ultimately results in cell death [14]. Through noradrenergic signaling, calcium dysregulation, and oxidative stress, aging makes neurons more susceptible to ER stress [15].

4. Apolipoprotein E (APOE) hypothesis

APOE plays a role in the regular breakdown of lipoproteins and the transport of fat and fat-soluble substances to the lymphatic system. It is initially synthesized in the brain and liver. The three alleles of the APOE gene (ε2=8%, ε3=77%, and ε4=15%) are found on chromosome 19. AD was also linked to APOE ε4 [16]. APOE ε4 exacerbates glymphatic dysfunction by impairing AQP4 polarization [8], while also promoting neuroinflammation through microglial NF-κB activation [16]. This dual effect accelerates Aβ/tau accumulation, suggesting lipid-targeted therapies (e.g., bexarotene) may benefit ε4 carriers specifically. It also causes BBB disruption, synaptic and metabolic dysfunction [6].

Aging alters the expression and function of APOE, leading to reduced lipid transport efficiency, impaired neuronal repair, and increased vulnerability to neuroinflammation and Aβ accumulation, particularly in individuals carrying the APOE ε4 allele [17].

5. Neurotrophic factor hypothesis

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is essential for immune system lifespan, learning, memory, and sleep [18]. The action of BDNF on tropomyosin receptor kinase B sustains long-term potentiation. Neuronal degeneration and impaired memory formation can result from changes in tropomyosin receptor kinase B receptor levels or BDNF expression [19].

Both AD and aging are associated with a decline in BDNF expression and signaling, which exacerbates neurodegeneration by diminishing neuronal survival, growth, and repair mechanisms [18]. Therapeutic strategies to restore BDNF activity include physical exercise, cognitive training, and dietary polyphenols, which offer the potential to counteract synaptic loss and cognitive decline in aging and AD.

6. Excitotoxic hypothesis

Glutamate, an excitatory neurotransmitter, is essential for memory and learning. It has both ionotropic (NMDA) and metabotropic receptors. AD is influenced by the NMDA ionotropic glutamate receptors. During the resting membrane potential, magnesium ions block the voltage-dependent calcium channels of NMDA receptors. During depolarization, this barrier is removed, allowing calcium to enter the cell. The decrease in glutamate recycling in AD causes hyperexcitation of these receptors. These processes cause cell death and damage to neurons by increasing calcium influx [20].

Glutamate transporter dysfunction, elevated synaptic glutamate levels, and excitotoxic susceptibility are all associated with aging [21]. Calcium-induced cell death cascades are accelerated in aging neurons due to a decreased mitochondrial buffer capacity [20].

Therapeutic implications: targeting aging to treat AD

Traditional therapeutic approaches for AD have primarily focused on reducing the Aβ burden or preventing p-tau aggregation. Despite decades of effort, these strategies have yielded limited clinical success rates. In contrast, targeting upstream aging mechanisms offers a new therapeutic paradigm involving interventions that delay, prevent, or even reverse AD-related processes. These interventions may include a variety of lifestyle adjustments, biological and medical therapies.

Lifestyle modifications

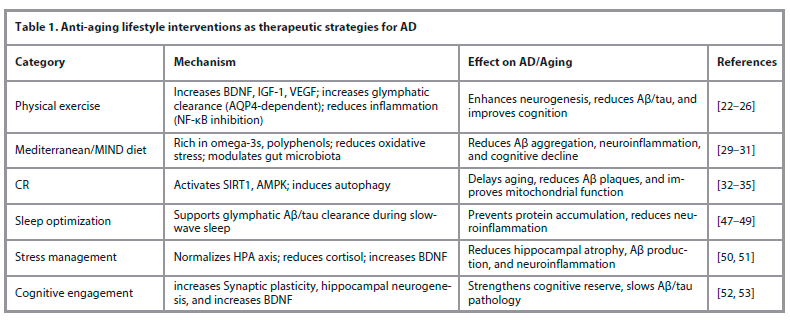

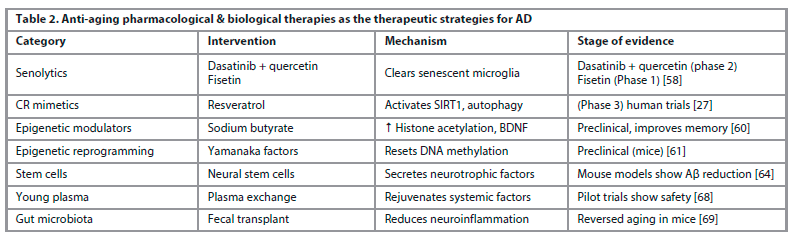

In order to maintain a normal weight and level of activity, lifestyle changes that incorporate physical activity, a balanced diet, restful sleep, stress management, and mental activity are generally safe and have been demonstrated to have neuroprotective effects (Table 1).

A. Physical activity

The most efficient non-pharmacological strategy to affect brain aging and AD risk is physical exercise, which includes morning gymnastics, walking, swimming, gardening, climbing stairs, and housework. Through the following processes, combined exercise training – including aerobic, strength, balance, and coordination training – as well as cognitive and social activities, appears to offer significant benefits to those with AD [22].

First, by upregulating BDNF, insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), exercise antagonists alter AD by improving neuroplasticity and expanding hippocampus volume [23]. These elements play a role in normal hippocampal regeneration and angiogenesis (regulated by IGF-1 and VEGF) as well as learning (regulated by IGF-1 and BDNF) [22]. It also enhances glymphatic clearance, promoting Aβ removal via AQP4-dependent mechanisms, which is particularly critical in APOE ε4 carriers [24]. BDNF depletion reduces TrkB-mediated synaptic resilience, worsening glutamate excitotoxicity. Exercise-induced BDNF upregulation may counteract this by enhancing calcium buffering [22].

Secondly, it improves mitochondrial biogenesis and glucose metabolism, which counteracts cerebral hypometabolism [25]. Finally, it exerts anti-inflammatory, anti-immunity, antioxidant, hippocampal insulin signaling, autophagy, and gut microbial ecosystem [26]. Gamma-aminobutyric acid, Aktare, irisin, dopamine, and other chemicals are involved in these mechanisms [23].

Exercise mimetics aim to replicate the cellular benefits of physical activity, such as mitochondrial biogenesis and insulin sensitivity, without physical exertion. However, they lack the full systemic effects of real exercise and may raise safety concerns with chronic use.

By promoting mitochondrial biogenesis and improving glucose metabolism, 5' adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activator lowers Aβ accumulation and enhances brain energy balance [27]. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta agonists (e.g., GW501516) regulate lipid and glucose homeostasis in the brain, improving insulin sensitivity, restoring synaptic function, and reducing pro-inflammatory cytokines [28].

However, despite the numerous mechanisms, further research is necessary to elucidate the exercise variables (including kind, volume, duration, and intensity) that influence AD.

B. Nutrition

In addition to providing vital nutrients for neuroprotection, eating a well-balanced diet full of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, lean meats, and healthy fats can help fight against insulin resistance, gut-brain axis dysfunction, and oxidative stress neuroinflammation [5].

Delays in cognitive decline and a lower risk of AD are linked to nutritional strategies such as the Mediterranean diet, the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet, the Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay (MIND), and the Stop Hypertension (GUSTO) diet. These diets are high in fiber, plant-based polyphenols, omega-3 fatty acids, vitamins E and B12, and low in saturated fats and refined sugars, all of which modulate the hallmarks of aging and neurodegeneration [29]. Omega-3 (polyunsaturated fatty acid) is integral to neuronal membrane integrity and has been shown to reduce Aβ aggregation, suppress pro-inflammatory cytokine production, promote synaptic plasticity, and reduce the risk of cognitive decline [27]. Royal jelly provides neuroprotection against tau and Aβ aggregation, especially with ageing through synaptic signal transduction, antioxidant system enhancement, inflammation suppression, and increased neurotrophin production–all of which support normal neuronal structure and function [30].

Dysbiosis with aging is linked to increased permeability of the gut and BBB, promoting systemic inflammation and AD pathology– a process that can be attenuated by probiotic, prebiotic, or fecal microbiota transplantation [31].

Reducing caloric intake by 20–60% without causing starvation is known as calorie restriction (CR). Mice's lifespan can be increased by up to 40% or more by delaying age-related diseases [32]. The degree of CR, the length of the diet, the age, sex, and general health status of the individual all affect how CR works [33].

Mechanisms that directly prevent aging-related AD pathogenesis include SIRT1 gene activation, enhanced insulin sensitivity, and autophagy induction [34]. CR combined with intermittent fasting is more effective in improving cognitive function and reducing Aβ accumulation [35].

CR mimetics are substances that, without actually lowering caloric intake, attempt to replicate the physiological effects of CR. Natural substances, including resveratrol, curcumin, and quercetin, as well as pharmaceutical medications like metformin, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists, rapamycin, and spermidine, are examples of CR mimetics [36].

Resveratrol, a natural polyphenolic chemical present in vegetables and fruits [27], has been shown to combat inflammation, oxidative stress, apoptosis, synaptic dysfunction, mitochondrial dysfunction, and angiogenesis [36]. Resveratrol also reduces Aβ aggregation, inhibits p-tau levels, and enhances mitochondrial biogenesis [27]. It has both physical activity and CR mimetics.

Metformin, a widely used AMPK activator for type 2 diabetes, promotes autophagy, reduces oxidative stress, and improves insulin sensitivity in the brain, counteracting insulin resistance often observed in early AD [37]. Some studies suggest that metformin reduces p-tau and neuroinflammation in animal models of AD [33].

Rapamycin, a mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor, delays brain aging by enhancing autophagy and lysosomal clearance of damaged proteins, including Aβ and p-tau. It also reduces microglial activation and inflammaging, which are exacerbated by age and contribute to cognitive decline [36].

Spermidine, a polyamine with CR-mimetic properties, increases autophagy and exerts neuroprotective effects in AD models by decreasing tau fibrillation and Aβ burden, boosting mitochondrial function, and improving memory [38].

Curcumin, the principal polyphenol in turmeric, exhibits anti-Aβ activity, antioxidant properties, anti-inflammatory effects, antiapoptotic functions, and modulation of cellular pathways through epigenetic processes. It binds to Aβ plaques, inhibits aggregation, promotes clearance, and modulates microglial activity [39].

Combinatorial methods can be used to increase curcumin's therapeutic effectiveness. For example, curcumin and ascorbic acid together increase the anti-inflammatory response [40].

Quercetin, a natural flavonoid found in fruits and vegetables, has antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects [41].

It produces its anti-inflammatory effects via activation of AMPK, which inhibits the activation of pro-inflammatory pathways. It also limits the damaging effects of inflammation on neuronal cells and improves mitochondrial function in mice with AD [42]. Quercetin also lowers Aβ aggregation, p-tau phosphorylation, and microglial activation. It restores acetylcholine levels through the inhibition of the hydrolysis of acetylcholine by the acetylcholinesterase enzyme [43].

Genistein, a soy-derived isoflavone, mimics the estrogenic effects of estrogen, providing neuroprotection in postmenopausal women. It has multimodal properties, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-amyloidogenic, anti-gut dysbiosis, pro-autophagy actions, and augmentation of neural plasticity [44].

Anthocyanins in blueberries, blackberries, and purple corn are neuroprotective, antioxidant (reducing oxidative stress, inhibiting Aβ aggregation), anti-inflammatory (decreasing proinflammatory signals), antiapoptotic, protecting the BBB, and promoting cholinergic neurotransmission. They enhance synaptic signaling, improve spatial working memory, and reduce tau pathology [45]. The metabolic rate of anthocyanins varies among individuals, potentially affecting their overall effectiveness [46].

C. Sleep

Sleep disruption affects the glymphatic system during slow-wave sleep, reducing the clearance of Aβ and p-tau [47]. It also increases pro-inflammatory cytokine levels, triggers ER stress, and disrupts synaptic homeostasis by reducing BDNF expression, leading to neurodegeneration and pathological progression [48]. Aging and AD disproportionately reduce slow-wave sleep, impair glymphatic system clearance, and create a vicious cycle of neurodegeneration [49].

D. Stress management

Chronic psychological stress contributes to AD pathogenesis via neuroendocrine, inflammatory, and structural mechanisms. By disrupting the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, aging intensifies these effects by raising cortisol levels, which impair long-term potentiation, diminish neurogenesis, and cause hippocampal atrophy – all of which are critical for memory [50]. Additionally, glucocorticoids stimulate Aβ production, enhance p-tau, and impair Aβ clearance while activating NF-κB-mediated neuroinflammation and microglial dysfunction, contributing to inflammaging and neuronal death [51].

It has been demonstrated that stress management techniques, including yoga, mindfulness, and cognitive behavioral therapy, raise BDNF expression, increase hippocampus volume, and return cortisol levels to normal [50].

E. Mental activity

Maintaining intellectual activity and mental activities can be achieved by regularly participating in mental activities like crossword puzzles, education, reading books and magazines, puzzle organization, playing games like chess, board, checkers, and cards, and taking music courses. These types aid in enhancing visual memory, learning capacity, logical reasoning, attention, focus, and perceptiveness [23].

Mechanistically, cognitive engagement enhances synaptic density, promotes dendritic complexity, upregulates BDNF, and supports hippocampal neurogenesis, creating structural resilience against neurodegeneration [52]. Cognitive enrichment has been demonstrated to lower Aβ burden and decrease functional decline in both human and animal models, including APOE ε4 carriers [26].

F. Sociostation

Aging often leads to social isolation, comparatively more isolation, and loneliness. These psychosocial deficits exacerbate HPA axis dysregulation, elevate cortisol levels, induce hippocampal atrophy, and intensify neuroinflammation, all of which contribute to accelerated neurodegeneration and Aβ/p-tau pathology [53].

Conversely, structured social programs – such as group therapy and intergenerational initiatives – improve mood and memory, reduce Aβ deposition, elevate BDNF expression, preserve long-term potentiation, and delay functional decline in AD patients [54].

G. Creativity

Mechanistically, creative interventions such as music, art, and dance enhance emotional regulation, support cognitive performance, and boost levels of BDNF and nerve growth factor in AD patients. These effects are mediated by reduced neuroinflammation and stress pathways [55].

Conclusion. The antiaging effects of AD may be enhanced by combining these lifestyle choices; however, even if lifestyle modifications appear promising, more research is required to confirm their safety, efficacy, recommended dosages, and potential interactions with other drugs.

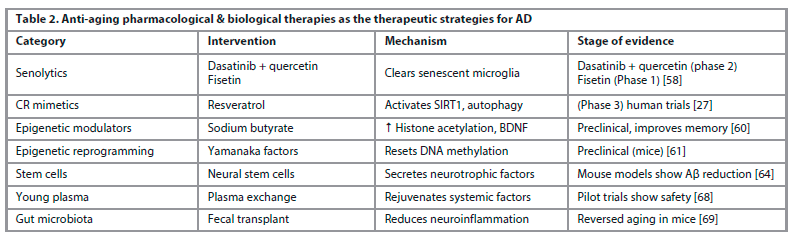

Medical therapies (Table 2)

Acupuncture. Because acupuncture improves neuroinflammation, synaptic plasticity, nerve cell death, and the brain's synthesis and aggregation of Aβ, it can help with memory and cognitive impairment in AD. It is considered non-invasive, generally safe, and associated with improved cognitive markers in small-scale trials [56].

Cellular senescence. It is defined as the irreversible growth arrest of damaged or stressed cells, which contributes significantly to age-related neurodegeneration through the release of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype – a mixture of chemokines, proteolytic enzymes, and cytokines [57].

Agents such as dasatinib, quercetin, and fisetin act as senolytics by targeting and removing aged or damaged cells associated with chronic inflammation. In mouse models of AD, these agents have been shown to reduce Aβ plaques, decrease tau aggregation, and improve cognitive performance [58].

On the other hand, senomorphics like rapamycin and metformin suppress the harmful senescence-associated secretory phenotype without inducing cell death, and have shown efficacy in reducing tau pathology and modulating neuroinflammation in preclinical settings [36]. There is some debate on the usefulness of senescence, despite its potential for treatment. Their inability to specifically eradicate senescent cells is the first drawback. Second, while senolytics may be less effective if used later, administering them too soon causes stem cell depletion, which speeds up the aging process and causes thrombocytopenia in the elderly. The type and quantity of senescent cells that should be eliminated for best results are also controversial [58].

Epigenetic aging and reprogramming. Age-related epigenetic changes, such as DNA methylation drift and histone modification alterations, can silence key neuroplasticity-related genes and are predictive of AD risk. Epigenetic clocks, especially the Horvath clock, serve as biomarkers of biological aging and correlate more closely with AD pathology than chronological age [59].

Histone deacetylase inhibitors, such as sodium butyrate, have been shown to restore histone acetylation, increase BDNF expression, and improve memory performance in AD models [60]. More recently, partial epigenetic reprogramming using Yamanaka factors has demonstrated reversal of age-associated DNA methylation patterns, reduced Aβ pathology, and enhanced cognitive function in murine models without inducing tumorigenesis [61].

Enhancing autophagy and proteostasis. Autophagy declines with age, leading to toxic protein accumulation. mTOR inhibition by rapamycin restores autophagy and reduces Aβ/p-tau pathology, improving cognition [44]. Natural compounds like spermidine, curcumin, and resveratrol also induce autophagy and show cognitive benefits [27]. Without adversely affecting other proteins such as the Notch receptor or amyloid precursor-like protein 1, the autophagy activator small-molecule enhancer of rapamycin-28 promotes the degradation of Aβ and the C-terminal segment of the amyloid precursor protein [44].

Hormonal therapy. Neuroprotective substances include insulin-like growth factor-2, growth hormone-releasing hormone, gonadotropin-releasing hormone, and estrogen. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone slows down aging and encourages neurogenesis in mice [3]. In AD models, insulin-like growth factor-2 improves cognition by promoting neurogenesis and synaptogenesis [62]. To reduce neuroinflammation and other AD pathologies, estrogen shields neurons from Aβ toxicity and glutamatergic excitotoxicity. Additionally, it regulates transcription factors, including nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 and NF-κB, that are connected to inflammation and oxidative stress [63].

Biological therapies

In addition to repairing nerve damage in AD, neural stem cells can also slow down aging and neurodegenerative disorders because of their capacity to develop into neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes. They have been demonstrated to improve pathogenic events and behaviors in AD mice and to reduce neuroinflammation, synaptic, and metabolic dysfunctions [64]. Furthermore, enkephalinase (neprilysin), which is secreted by adipose-derived stem cells, can directly break down Aβ plaques [65].

Young bone marrow transplantation helps older mice maintain synaptic connections, cytokine levels, and cognitive symptoms, extending their maximum lifespan by 30% [66]. However, the practical use of bone marrow transplantation is restricted by transplant rejection and the scarcity of young bone marrow donors [65].

In addition to reducing soluble Aβ levels in the blood and Aβ plaques in the brains of aged rats, whole blood replacement dramatically improves spatial memory [67]. Delivering a wider variety of antiaging agents that target several aging markers simultaneously is made possible by blood rejuvenation. Although it necessitates an adequate blood supply and may result in negative reactions, this strategy might be more effective [4]. Further study into long-term plasma therapy is necessary, as evidenced by the encouraging outcomes seen in AD patients who received four weekly infusions of young fresh frozen plasma [68].

When the gut microbiota of young mice is transplanted into older animals, immunosenescence and neuroinflammation are reversed, and hippocampal neurogenesis, behavior, and cognition are all improved (Table 2) [69].

Despite encouraging preclinical data, challenges remain. Ethical concerns, risk of tumorigenesis, immune rejection, and low survival rates post-transplantation must be addressed before clinical translation.

Other possible therapies

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs like Ibuprofen, antiviral medications like valacyclovir and some antibiotics, mitochondrial function regulators like nilotinib, metabolic activators like L-serine, N-acetyl cysteine, nicotinamide riboside, and L-carnitine tartrate, neural repair medications like CT1812 and simufilam, and antioxidants have been shown to have a neuroprotective effect and are being investigated for the treatment of AD [4].

Future directions and conclusion

AD can be viewed not just as a neurodegenerative condition but as a manifestation of accelerated brain aging. By targeting the root causes of aging through a geroscience framework, we have the opportunity to delay or even prevent AD onset. Rather than targeting downstream symptoms alone, emerging strategies seek to intervene earlier in the disease course by addressing the biological aging mechanisms that drive AD pathogenesis.

Future research should focus on integrated, multimodal interventions that combine lifestyle modification with pharmacological and biological therapies. Tailored approaches – based on genetic risk profiles (e.g., APOE status), comorbidities, and individual aging trajectories – may optimize clinical outcomes. To evaluate the long-term safety and effectiveness of innovative treatments like senolytics, epigenetic modulators, and stem cell-based therapies in older populations, extensive, longitudinal clinical trials are also required. Developments in biological age biomarkers, machine learning, and systems biology have the potential to improve risk assessment and therapy customization.

Информация об авторе

Information about the author

Халед А. Абдель-Шатер – доктор медицины, стоматологический факультет, Университет Мута.

E-mail: Kabdelsater@mutah.edu.jo; ORCID: 0000-0001-9357-4983

Khaled A. Abdel-Sater – MD, Faculty of Dentistry, Mutah University. E-mail: Kabdelsater@mutah.edu.jo; ORCID: 0000-0001-9357-4983

Поступила в редакцию: 20.07.2025

Поступила после рецензирования: 04.08.2025

Принята к публикации: 14.08.2025

Received: 20.07.2025

Revised: 04.08.2025

Accepted: 14.08.2025

Клинический разбор в общей медицине №8 2025

Геронтологические подходы к болезни Альцгеймера: терапевтическое вмешательство в процессы старения

Номера страниц в выпуске:22-30

Аннотация

Актуальность. Самым значимым фактором риска развития болезни Альцгеймера (БА) является старение, которое способствует нарушению процесса выведения тау-белка и бета-амилоида из организма, вносит свой вклад в старение клеток микроглии, стресс эндоплазматического ретикулума, нарушение регуляции липидного обмена и эксайтотоксичность.

Цель. Рассмотреть, как старение ускоряет патофизиологические процессы при БА, представить оценку новых геронтологических вмешательств, воздействующих на механизмы биологического старения с целью отсрочить или предотвратить когнитивные нарушения.

Методы. Выполнен описательный обзор литературы за 2015–2025 гг., в который включены продольные исследования, метаанализы и доклинические модели взаимосвязи между старением и БА. Поиск осуществляли в базах данных MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane, Google Scholar и PubMed, используя непосредственно связанные с тематикой обзора ключевые слова: старение, БА, патология БА, антивозрастные стратегии и средства для лечения БА.

Результаты. После первоначального поиска исключили более 150 исследований. Только 100 исследований были отобраны для обзора. После проверки исключили еще 30 дублировавшихся исследований. В конечном итоге в исследование были включены 70 исследований. Большая часть этих исследований посвящена изучению связанных со старением механизмов – глимфатической дисфункции, APOE ε4-ассоциированного нарушения транспорта липидов, истощения BDNF и эксайтотоксичности глутамата, а также антивозрастных стратегий, таких как вмешательства в образ жизни (например, физическая активность, оптимизация сна, познавательная вовлеченность) и медицинских и биологических методов лечения БА.

Выводы. Воздействие на механизмы старения предлагает принципиально новое видение профилактики и лечения БА, однако для того, чтобы перейти от геронауки к клинической практике, необходимо междисциплинарное сотрудничество. Интегрирование образа жизни и медикаментозных стратегий может обеспечить полезный синергический нейропротективный эффект. Дальнейшие исследования должны быть посвящены изучению интегрированных мультимодальных вмешательств, представляющих собой сочетание изменения образа жизни с фармакологическими и биологическими методами лечения. Индивидуальный подход, основанный на оценке генетических рисков (в том числе генотипа APOE), сопутствующих заболеваний и индивидуальной траектории старения, может способствовать оптимизации клинических исходов. Помимо этого для оценки безопасности и эффективности новейших терапевтических средств, таких как сенолитики, модуляторы эпигенетических процессов и терапия стволовыми клетками, в популяции пожилых людей в долгосрочной перспективе необходимы широкомасштабные продольные клинические исследования. Разработки в области биомаркеров биологического возраста, машинного обучения и системной биологии могут способствовать совершенствованию оценки рисков и персонализации терапии.

Ключевые слова: болезнь Альцгеймера, старение, нейровоспаление, сенолитики, эпигенетика, терапия стволовыми клетками.

Для цитирования: Абдель-Шатер Х.А. Геронтологические подходы к болезни Альцгеймера: терапевтическое вмешательство в процессы старения. Клинический разбор в общей медицине. 2025; 6 (8): 22–30. DOI: 10.47407/kr2025.6.8.00654

Актуальность. Самым значимым фактором риска развития болезни Альцгеймера (БА) является старение, которое способствует нарушению процесса выведения тау-белка и бета-амилоида из организма, вносит свой вклад в старение клеток микроглии, стресс эндоплазматического ретикулума, нарушение регуляции липидного обмена и эксайтотоксичность.

Цель. Рассмотреть, как старение ускоряет патофизиологические процессы при БА, представить оценку новых геронтологических вмешательств, воздействующих на механизмы биологического старения с целью отсрочить или предотвратить когнитивные нарушения.

Методы. Выполнен описательный обзор литературы за 2015–2025 гг., в который включены продольные исследования, метаанализы и доклинические модели взаимосвязи между старением и БА. Поиск осуществляли в базах данных MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane, Google Scholar и PubMed, используя непосредственно связанные с тематикой обзора ключевые слова: старение, БА, патология БА, антивозрастные стратегии и средства для лечения БА.

Результаты. После первоначального поиска исключили более 150 исследований. Только 100 исследований были отобраны для обзора. После проверки исключили еще 30 дублировавшихся исследований. В конечном итоге в исследование были включены 70 исследований. Большая часть этих исследований посвящена изучению связанных со старением механизмов – глимфатической дисфункции, APOE ε4-ассоциированного нарушения транспорта липидов, истощения BDNF и эксайтотоксичности глутамата, а также антивозрастных стратегий, таких как вмешательства в образ жизни (например, физическая активность, оптимизация сна, познавательная вовлеченность) и медицинских и биологических методов лечения БА.

Выводы. Воздействие на механизмы старения предлагает принципиально новое видение профилактики и лечения БА, однако для того, чтобы перейти от геронауки к клинической практике, необходимо междисциплинарное сотрудничество. Интегрирование образа жизни и медикаментозных стратегий может обеспечить полезный синергический нейропротективный эффект. Дальнейшие исследования должны быть посвящены изучению интегрированных мультимодальных вмешательств, представляющих собой сочетание изменения образа жизни с фармакологическими и биологическими методами лечения. Индивидуальный подход, основанный на оценке генетических рисков (в том числе генотипа APOE), сопутствующих заболеваний и индивидуальной траектории старения, может способствовать оптимизации клинических исходов. Помимо этого для оценки безопасности и эффективности новейших терапевтических средств, таких как сенолитики, модуляторы эпигенетических процессов и терапия стволовыми клетками, в популяции пожилых людей в долгосрочной перспективе необходимы широкомасштабные продольные клинические исследования. Разработки в области биомаркеров биологического возраста, машинного обучения и системной биологии могут способствовать совершенствованию оценки рисков и персонализации терапии.

Ключевые слова: болезнь Альцгеймера, старение, нейровоспаление, сенолитики, эпигенетика, терапия стволовыми клетками.

Для цитирования: Абдель-Шатер Х.А. Геронтологические подходы к болезни Альцгеймера: терапевтическое вмешательство в процессы старения. Клинический разбор в общей медицине. 2025; 6 (8): 22–30. DOI: 10.47407/kr2025.6.8.00654

Geroscience-guided approaches for Alzheimer’s disease: targeting aging mechanisms for therapeutic intervention

Khaled A. Abdel-SaterMutah University, Al-Karak, Jordan

Kabdelsater@mutah.edu.jo

Abstract

Background. The biggest risk factor for Alzheimer's disease (AD) is aging, contributing to impaired clearance of tau and amyloid-beta proteins, microglial senescence, endoplasmic reticulum stress, lipid dysregulation, and excitotoxicity.

Objective. This review investigates how aging speeds up the pathophysiology of AD and evaluates emerging geroscience-based interventions targeting biological aging mechanisms to delay or prevent cognitive decline.

Methods. A narrative review of the literature from 2015 to 2025 was conducted, integrating longitudinal studies, meta-analyses, and preclinical models that examine the aging-AD interface. The MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane, Google Scholar, and PubMed databases were searched using specifically related keywords, such as ageing, AD, AD pathology, anti-aging strategies, and AD therapies.

Results. From the initial search, more than 150 studies were excluded, and only 100 studies were selected for this review. After revision also duplicated 30 studies were removed. Ultimately, the review comprised seventy studies. Most of these studies discussed aging-related mechanisms – glymphatic dysfunction, APOE ε4-associated lipid transport impairment, BDNF depletion, and glutamate excitotoxicity, and anti-ageing strategies such as lifestyle interventions (e.g., physical activity, sleep optimization, cognitive engagement) and medical and biological therapies for AD.

Conclusion. Targeting aging mechanisms offers a paradigm shift in AD prevention and treatment; however, multidisciplinary collaboration is essential to translate geroscience into clinical practice. The integration of lifestyle and pharmacological strategies may yield synergistic neuroprotective benefits. Future research should focus on integrated, multimodal interventions that combine lifestyle modification with pharmacological and biological therapies. Tailored approaches–based on genetic risk profiles (e.g., APOE status), comorbidities, and individual aging trajectories–may optimize clinical outcomes. To evaluate the long-term safety and effectiveness of innovative treatments like senolytics, epigenetic modulators, and stem cell-based therapies in older populations, extensive, longitudinal clinical trials are also required. Developments in biological age biomarkers, machine learning, and systems biology have the potential to improve risk assessment and therapy customization.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, aging, neuroinflammation, senolytics, epigenetics, stem cell therapy.

For citation: Abdel-Sater K.A. Geroscience-guided approaches for Alzheimer’s disease: targeting aging mechanisms for therapeutic intervention. Clinical review for general practice. 2025; 6 (8): 22–30 (In Russ.). DOI: 10.47407/kr2025.6.8.00654

Introduction

Between 60% and 80% of dementia cases worldwide are caused by Alzheimer's disease (AD), making it the most prevalent type of dementia [1]. As of 2025, approximately 60 million people worldwide are affected by dementia, and by 2050, projections suggest a rise to nearly 210 million 2050 [2]. Age is the strongest risk factor, with AD affecting nearly half of those aged >85 years [3]. In both the United States and Europe, the prevalence of AD increases with age, from 0.85% among individuals aged 65–69 years to 44.35% in those aged over 95 years [4].

In addition to aging, Fig. 1 shows several other factors that contribute to AD risk, including female sex, genetic predisposition, low educational attainment, head injuries, and lifestyle-related behaviors such as a sedentary lifestyle, smoking, alcohol use, and obesity. These risk factors synergistically interact with aging to promote the development of AD [5].

Despite years of research, the treatment of AD remains limited. This highlights the need for novel approaches that target the underlying pathophysiology. The biggest risk factor for AD is aging, and targeting aging processes may be more successful than Aβ/p-tau strategies in altering the course of AD. This review critically evaluates the biological pathways through which aging contributes to AD pathogenesis and examines innovative lifestyle and pharmacological interventions that target these processes.

AD pathology: possible role of ageing

Aging induces systemic biological changes that disrupt homeostasis at the molecular, cellular, and tissue levels. These alterations include mitochondrial dysfunction, impaired proteostasis, genomic instability, oxidative stress, inflammation, and reduced regenerative capacity. In the brain, aging disrupts proteostasis, synaptic function, immune surveillance, metabolism, and the blood-brain barrier's (BBB) integrity [3]. The formation and clearance of amyloid-beta (Aβ) and phosphorylated tau (p-tau), neurotransmitter synthesis and release, microglial and astrocyte responses, neuronal excitability and plasticity, gut microbiota functions, and autophagy are all rapidly disrupted by these age-related changes – including oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and BBB breakdown–disrupt protein clearance, synaptic function, and immune regulation, ultimately driving AD progression (Fig. 2) [4].

1. Impairment of the Aβ/p-tau clearance and the glymphatic system

Aβ A is an acquired biomarker that can be used to predict disease because it appears a long time before the clinical signs of AD [6]. Under normal physiological conditions, Aβ is produced by neurons and efficiently removed via the glymphatic flow during sleep [7]. At normal levels, Aβ has numerous vital functions, including neuroprotection, memory improvement, and neuronal growth and repair. The accumulation of Aβ plaques is due to an imbalance between production and clearance. Its accumulation activates immune responses, causing neuronal destruction and memory impairment [6]. p-tau interacts with Aβ, exacerbating neurodegeneration through processes such as hyperphosphorylation [7].

With advancing age, several structural and functional changes compromise the glymphatic efficiency. These include reduced aquaporin-4 (AQP4) polarization, diminished arterial pulsatility, and impaired cerebrospinal fluid and interstitial fluid exchange. Consequently, aged brains exhibit reduced clearance of Aβ, facilitating its aggregation into extracellular plaques, which is a defining feature of early AD pathology [8].

Experimental evidence from aged rodent models and human neuroimaging studies has demonstrated a significant decline in glymphatic clearance, which correlates with an increased Aβ burden. Interventions that improve sleep architecture, enhance vascular function, or stimulate AQP4 expression are being explored as therapeutic strategies to restore the glymphatic function and slow AD progression [6].

2. Microglial dysfunction and immune dysregulation in aging

The brain's macrophages, known as microglia, are essential for preserving the homeostasis of the central nervous system because they monitor the surroundings, control inflammatory reactions, remove debris, including Aβ, and promote synaptic plasticity [9].

However, with aging, microglia undergo functional decline, shifting from a neuroprotective to a pro-inflammatory state due to transcriptional changes that upregulate inflammatory genes while downregulating homeostatic genes [10]. This dysfunction is exacerbated by reduced phagocytic efficiency, which impairs the clearance of Aβ and contributes to plaque accumulation, neurotoxicity, and tau pathology [8].

At the same time, pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1 (IL-1β), IL-6, tumor necrosis factor-α, and -γ are elevated due to systemic immunological dysregulation in aging, which impairs memory formation, synaptic integrity, and neuronal function [11]. Central to this process is the transcription factor nuclear factor κB (NF-κB), which is activated by oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and cellular senescence, which perpetuates inflammatory signaling. Together, microglial dysfunction and immune dysregulation create a vicious cycle of chronic inflammation and neuronal damage, accelerating age-related cognitive decline [12]. Therapeutic approaches aimed at reducing microglial senescence, including senolytic therapy, may reduce neuroinflammation and restore microglial homeostasis, offering a promising avenue for age-related AD therapy.

3. Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and apoptosis

The ER is crucial for protein folding, calcium homeostasis, and lipid synthesis. Under normal conditions, the ER maintains proteostasis via a tightly regulated quality control system. With aging, protein misfolding and metabolic stress increase, neurofibrillary tangles destabilize microtubules, and induce p-tau. Aβ is also produced through the overexpression of beta-site amyloid precursor protein-cleaving enzyme 1 [13].

A distinct initial imbalance or shock of aberrant proteins triggers apoptosis by activating caspases via extrinsic and intrinsic (mitochondrial) pathways, which ultimately results in cell death [14]. Through noradrenergic signaling, calcium dysregulation, and oxidative stress, aging makes neurons more susceptible to ER stress [15].

4. Apolipoprotein E (APOE) hypothesis

APOE plays a role in the regular breakdown of lipoproteins and the transport of fat and fat-soluble substances to the lymphatic system. It is initially synthesized in the brain and liver. The three alleles of the APOE gene (ε2=8%, ε3=77%, and ε4=15%) are found on chromosome 19. AD was also linked to APOE ε4 [16]. APOE ε4 exacerbates glymphatic dysfunction by impairing AQP4 polarization [8], while also promoting neuroinflammation through microglial NF-κB activation [16]. This dual effect accelerates Aβ/tau accumulation, suggesting lipid-targeted therapies (e.g., bexarotene) may benefit ε4 carriers specifically. It also causes BBB disruption, synaptic and metabolic dysfunction [6].

Aging alters the expression and function of APOE, leading to reduced lipid transport efficiency, impaired neuronal repair, and increased vulnerability to neuroinflammation and Aβ accumulation, particularly in individuals carrying the APOE ε4 allele [17].

5. Neurotrophic factor hypothesis

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is essential for immune system lifespan, learning, memory, and sleep [18]. The action of BDNF on tropomyosin receptor kinase B sustains long-term potentiation. Neuronal degeneration and impaired memory formation can result from changes in tropomyosin receptor kinase B receptor levels or BDNF expression [19].

Both AD and aging are associated with a decline in BDNF expression and signaling, which exacerbates neurodegeneration by diminishing neuronal survival, growth, and repair mechanisms [18]. Therapeutic strategies to restore BDNF activity include physical exercise, cognitive training, and dietary polyphenols, which offer the potential to counteract synaptic loss and cognitive decline in aging and AD.

6. Excitotoxic hypothesis

Glutamate, an excitatory neurotransmitter, is essential for memory and learning. It has both ionotropic (NMDA) and metabotropic receptors. AD is influenced by the NMDA ionotropic glutamate receptors. During the resting membrane potential, magnesium ions block the voltage-dependent calcium channels of NMDA receptors. During depolarization, this barrier is removed, allowing calcium to enter the cell. The decrease in glutamate recycling in AD causes hyperexcitation of these receptors. These processes cause cell death and damage to neurons by increasing calcium influx [20].

Glutamate transporter dysfunction, elevated synaptic glutamate levels, and excitotoxic susceptibility are all associated with aging [21]. Calcium-induced cell death cascades are accelerated in aging neurons due to a decreased mitochondrial buffer capacity [20].

Therapeutic implications: targeting aging to treat AD

Traditional therapeutic approaches for AD have primarily focused on reducing the Aβ burden or preventing p-tau aggregation. Despite decades of effort, these strategies have yielded limited clinical success rates. In contrast, targeting upstream aging mechanisms offers a new therapeutic paradigm involving interventions that delay, prevent, or even reverse AD-related processes. These interventions may include a variety of lifestyle adjustments, biological and medical therapies.

Lifestyle modifications

In order to maintain a normal weight and level of activity, lifestyle changes that incorporate physical activity, a balanced diet, restful sleep, stress management, and mental activity are generally safe and have been demonstrated to have neuroprotective effects (Table 1).

A. Physical activity

The most efficient non-pharmacological strategy to affect brain aging and AD risk is physical exercise, which includes morning gymnastics, walking, swimming, gardening, climbing stairs, and housework. Through the following processes, combined exercise training – including aerobic, strength, balance, and coordination training – as well as cognitive and social activities, appears to offer significant benefits to those with AD [22].

First, by upregulating BDNF, insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), exercise antagonists alter AD by improving neuroplasticity and expanding hippocampus volume [23]. These elements play a role in normal hippocampal regeneration and angiogenesis (regulated by IGF-1 and VEGF) as well as learning (regulated by IGF-1 and BDNF) [22]. It also enhances glymphatic clearance, promoting Aβ removal via AQP4-dependent mechanisms, which is particularly critical in APOE ε4 carriers [24]. BDNF depletion reduces TrkB-mediated synaptic resilience, worsening glutamate excitotoxicity. Exercise-induced BDNF upregulation may counteract this by enhancing calcium buffering [22].

Secondly, it improves mitochondrial biogenesis and glucose metabolism, which counteracts cerebral hypometabolism [25]. Finally, it exerts anti-inflammatory, anti-immunity, antioxidant, hippocampal insulin signaling, autophagy, and gut microbial ecosystem [26]. Gamma-aminobutyric acid, Aktare, irisin, dopamine, and other chemicals are involved in these mechanisms [23].

Exercise mimetics aim to replicate the cellular benefits of physical activity, such as mitochondrial biogenesis and insulin sensitivity, without physical exertion. However, they lack the full systemic effects of real exercise and may raise safety concerns with chronic use.

By promoting mitochondrial biogenesis and improving glucose metabolism, 5' adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activator lowers Aβ accumulation and enhances brain energy balance [27]. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta agonists (e.g., GW501516) regulate lipid and glucose homeostasis in the brain, improving insulin sensitivity, restoring synaptic function, and reducing pro-inflammatory cytokines [28].

However, despite the numerous mechanisms, further research is necessary to elucidate the exercise variables (including kind, volume, duration, and intensity) that influence AD.

B. Nutrition

In addition to providing vital nutrients for neuroprotection, eating a well-balanced diet full of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, lean meats, and healthy fats can help fight against insulin resistance, gut-brain axis dysfunction, and oxidative stress neuroinflammation [5].

Delays in cognitive decline and a lower risk of AD are linked to nutritional strategies such as the Mediterranean diet, the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet, the Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay (MIND), and the Stop Hypertension (GUSTO) diet. These diets are high in fiber, plant-based polyphenols, omega-3 fatty acids, vitamins E and B12, and low in saturated fats and refined sugars, all of which modulate the hallmarks of aging and neurodegeneration [29]. Omega-3 (polyunsaturated fatty acid) is integral to neuronal membrane integrity and has been shown to reduce Aβ aggregation, suppress pro-inflammatory cytokine production, promote synaptic plasticity, and reduce the risk of cognitive decline [27]. Royal jelly provides neuroprotection against tau and Aβ aggregation, especially with ageing through synaptic signal transduction, antioxidant system enhancement, inflammation suppression, and increased neurotrophin production–all of which support normal neuronal structure and function [30].

Dysbiosis with aging is linked to increased permeability of the gut and BBB, promoting systemic inflammation and AD pathology– a process that can be attenuated by probiotic, prebiotic, or fecal microbiota transplantation [31].

Reducing caloric intake by 20–60% without causing starvation is known as calorie restriction (CR). Mice's lifespan can be increased by up to 40% or more by delaying age-related diseases [32]. The degree of CR, the length of the diet, the age, sex, and general health status of the individual all affect how CR works [33].

Mechanisms that directly prevent aging-related AD pathogenesis include SIRT1 gene activation, enhanced insulin sensitivity, and autophagy induction [34]. CR combined with intermittent fasting is more effective in improving cognitive function and reducing Aβ accumulation [35].

CR mimetics are substances that, without actually lowering caloric intake, attempt to replicate the physiological effects of CR. Natural substances, including resveratrol, curcumin, and quercetin, as well as pharmaceutical medications like metformin, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists, rapamycin, and spermidine, are examples of CR mimetics [36].

Resveratrol, a natural polyphenolic chemical present in vegetables and fruits [27], has been shown to combat inflammation, oxidative stress, apoptosis, synaptic dysfunction, mitochondrial dysfunction, and angiogenesis [36]. Resveratrol also reduces Aβ aggregation, inhibits p-tau levels, and enhances mitochondrial biogenesis [27]. It has both physical activity and CR mimetics.

Metformin, a widely used AMPK activator for type 2 diabetes, promotes autophagy, reduces oxidative stress, and improves insulin sensitivity in the brain, counteracting insulin resistance often observed in early AD [37]. Some studies suggest that metformin reduces p-tau and neuroinflammation in animal models of AD [33].

Rapamycin, a mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor, delays brain aging by enhancing autophagy and lysosomal clearance of damaged proteins, including Aβ and p-tau. It also reduces microglial activation and inflammaging, which are exacerbated by age and contribute to cognitive decline [36].

Spermidine, a polyamine with CR-mimetic properties, increases autophagy and exerts neuroprotective effects in AD models by decreasing tau fibrillation and Aβ burden, boosting mitochondrial function, and improving memory [38].

Curcumin, the principal polyphenol in turmeric, exhibits anti-Aβ activity, antioxidant properties, anti-inflammatory effects, antiapoptotic functions, and modulation of cellular pathways through epigenetic processes. It binds to Aβ plaques, inhibits aggregation, promotes clearance, and modulates microglial activity [39].

Combinatorial methods can be used to increase curcumin's therapeutic effectiveness. For example, curcumin and ascorbic acid together increase the anti-inflammatory response [40].

Quercetin, a natural flavonoid found in fruits and vegetables, has antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects [41].

It produces its anti-inflammatory effects via activation of AMPK, which inhibits the activation of pro-inflammatory pathways. It also limits the damaging effects of inflammation on neuronal cells and improves mitochondrial function in mice with AD [42]. Quercetin also lowers Aβ aggregation, p-tau phosphorylation, and microglial activation. It restores acetylcholine levels through the inhibition of the hydrolysis of acetylcholine by the acetylcholinesterase enzyme [43].

Genistein, a soy-derived isoflavone, mimics the estrogenic effects of estrogen, providing neuroprotection in postmenopausal women. It has multimodal properties, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-amyloidogenic, anti-gut dysbiosis, pro-autophagy actions, and augmentation of neural plasticity [44].

Anthocyanins in blueberries, blackberries, and purple corn are neuroprotective, antioxidant (reducing oxidative stress, inhibiting Aβ aggregation), anti-inflammatory (decreasing proinflammatory signals), antiapoptotic, protecting the BBB, and promoting cholinergic neurotransmission. They enhance synaptic signaling, improve spatial working memory, and reduce tau pathology [45]. The metabolic rate of anthocyanins varies among individuals, potentially affecting their overall effectiveness [46].

C. Sleep

Sleep disruption affects the glymphatic system during slow-wave sleep, reducing the clearance of Aβ and p-tau [47]. It also increases pro-inflammatory cytokine levels, triggers ER stress, and disrupts synaptic homeostasis by reducing BDNF expression, leading to neurodegeneration and pathological progression [48]. Aging and AD disproportionately reduce slow-wave sleep, impair glymphatic system clearance, and create a vicious cycle of neurodegeneration [49].

D. Stress management

Chronic psychological stress contributes to AD pathogenesis via neuroendocrine, inflammatory, and structural mechanisms. By disrupting the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, aging intensifies these effects by raising cortisol levels, which impair long-term potentiation, diminish neurogenesis, and cause hippocampal atrophy – all of which are critical for memory [50]. Additionally, glucocorticoids stimulate Aβ production, enhance p-tau, and impair Aβ clearance while activating NF-κB-mediated neuroinflammation and microglial dysfunction, contributing to inflammaging and neuronal death [51].

It has been demonstrated that stress management techniques, including yoga, mindfulness, and cognitive behavioral therapy, raise BDNF expression, increase hippocampus volume, and return cortisol levels to normal [50].

E. Mental activity

Maintaining intellectual activity and mental activities can be achieved by regularly participating in mental activities like crossword puzzles, education, reading books and magazines, puzzle organization, playing games like chess, board, checkers, and cards, and taking music courses. These types aid in enhancing visual memory, learning capacity, logical reasoning, attention, focus, and perceptiveness [23].

Mechanistically, cognitive engagement enhances synaptic density, promotes dendritic complexity, upregulates BDNF, and supports hippocampal neurogenesis, creating structural resilience against neurodegeneration [52]. Cognitive enrichment has been demonstrated to lower Aβ burden and decrease functional decline in both human and animal models, including APOE ε4 carriers [26].

F. Sociostation

Aging often leads to social isolation, comparatively more isolation, and loneliness. These psychosocial deficits exacerbate HPA axis dysregulation, elevate cortisol levels, induce hippocampal atrophy, and intensify neuroinflammation, all of which contribute to accelerated neurodegeneration and Aβ/p-tau pathology [53].

Conversely, structured social programs – such as group therapy and intergenerational initiatives – improve mood and memory, reduce Aβ deposition, elevate BDNF expression, preserve long-term potentiation, and delay functional decline in AD patients [54].

G. Creativity

Mechanistically, creative interventions such as music, art, and dance enhance emotional regulation, support cognitive performance, and boost levels of BDNF and nerve growth factor in AD patients. These effects are mediated by reduced neuroinflammation and stress pathways [55].

Conclusion. The antiaging effects of AD may be enhanced by combining these lifestyle choices; however, even if lifestyle modifications appear promising, more research is required to confirm their safety, efficacy, recommended dosages, and potential interactions with other drugs.

Medical therapies (Table 2)

Acupuncture. Because acupuncture improves neuroinflammation, synaptic plasticity, nerve cell death, and the brain's synthesis and aggregation of Aβ, it can help with memory and cognitive impairment in AD. It is considered non-invasive, generally safe, and associated with improved cognitive markers in small-scale trials [56].

Cellular senescence. It is defined as the irreversible growth arrest of damaged or stressed cells, which contributes significantly to age-related neurodegeneration through the release of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype – a mixture of chemokines, proteolytic enzymes, and cytokines [57].

Agents such as dasatinib, quercetin, and fisetin act as senolytics by targeting and removing aged or damaged cells associated with chronic inflammation. In mouse models of AD, these agents have been shown to reduce Aβ plaques, decrease tau aggregation, and improve cognitive performance [58].

On the other hand, senomorphics like rapamycin and metformin suppress the harmful senescence-associated secretory phenotype without inducing cell death, and have shown efficacy in reducing tau pathology and modulating neuroinflammation in preclinical settings [36]. There is some debate on the usefulness of senescence, despite its potential for treatment. Their inability to specifically eradicate senescent cells is the first drawback. Second, while senolytics may be less effective if used later, administering them too soon causes stem cell depletion, which speeds up the aging process and causes thrombocytopenia in the elderly. The type and quantity of senescent cells that should be eliminated for best results are also controversial [58].

Epigenetic aging and reprogramming. Age-related epigenetic changes, such as DNA methylation drift and histone modification alterations, can silence key neuroplasticity-related genes and are predictive of AD risk. Epigenetic clocks, especially the Horvath clock, serve as biomarkers of biological aging and correlate more closely with AD pathology than chronological age [59].

Histone deacetylase inhibitors, such as sodium butyrate, have been shown to restore histone acetylation, increase BDNF expression, and improve memory performance in AD models [60]. More recently, partial epigenetic reprogramming using Yamanaka factors has demonstrated reversal of age-associated DNA methylation patterns, reduced Aβ pathology, and enhanced cognitive function in murine models without inducing tumorigenesis [61].

Enhancing autophagy and proteostasis. Autophagy declines with age, leading to toxic protein accumulation. mTOR inhibition by rapamycin restores autophagy and reduces Aβ/p-tau pathology, improving cognition [44]. Natural compounds like spermidine, curcumin, and resveratrol also induce autophagy and show cognitive benefits [27]. Without adversely affecting other proteins such as the Notch receptor or amyloid precursor-like protein 1, the autophagy activator small-molecule enhancer of rapamycin-28 promotes the degradation of Aβ and the C-terminal segment of the amyloid precursor protein [44].

Hormonal therapy. Neuroprotective substances include insulin-like growth factor-2, growth hormone-releasing hormone, gonadotropin-releasing hormone, and estrogen. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone slows down aging and encourages neurogenesis in mice [3]. In AD models, insulin-like growth factor-2 improves cognition by promoting neurogenesis and synaptogenesis [62]. To reduce neuroinflammation and other AD pathologies, estrogen shields neurons from Aβ toxicity and glutamatergic excitotoxicity. Additionally, it regulates transcription factors, including nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 and NF-κB, that are connected to inflammation and oxidative stress [63].

Biological therapies

In addition to repairing nerve damage in AD, neural stem cells can also slow down aging and neurodegenerative disorders because of their capacity to develop into neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes. They have been demonstrated to improve pathogenic events and behaviors in AD mice and to reduce neuroinflammation, synaptic, and metabolic dysfunctions [64]. Furthermore, enkephalinase (neprilysin), which is secreted by adipose-derived stem cells, can directly break down Aβ plaques [65].

Young bone marrow transplantation helps older mice maintain synaptic connections, cytokine levels, and cognitive symptoms, extending their maximum lifespan by 30% [66]. However, the practical use of bone marrow transplantation is restricted by transplant rejection and the scarcity of young bone marrow donors [65].

In addition to reducing soluble Aβ levels in the blood and Aβ plaques in the brains of aged rats, whole blood replacement dramatically improves spatial memory [67]. Delivering a wider variety of antiaging agents that target several aging markers simultaneously is made possible by blood rejuvenation. Although it necessitates an adequate blood supply and may result in negative reactions, this strategy might be more effective [4]. Further study into long-term plasma therapy is necessary, as evidenced by the encouraging outcomes seen in AD patients who received four weekly infusions of young fresh frozen plasma [68].

When the gut microbiota of young mice is transplanted into older animals, immunosenescence and neuroinflammation are reversed, and hippocampal neurogenesis, behavior, and cognition are all improved (Table 2) [69].

Despite encouraging preclinical data, challenges remain. Ethical concerns, risk of tumorigenesis, immune rejection, and low survival rates post-transplantation must be addressed before clinical translation.

Other possible therapies

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs like Ibuprofen, antiviral medications like valacyclovir and some antibiotics, mitochondrial function regulators like nilotinib, metabolic activators like L-serine, N-acetyl cysteine, nicotinamide riboside, and L-carnitine tartrate, neural repair medications like CT1812 and simufilam, and antioxidants have been shown to have a neuroprotective effect and are being investigated for the treatment of AD [4].

Future directions and conclusion

AD can be viewed not just as a neurodegenerative condition but as a manifestation of accelerated brain aging. By targeting the root causes of aging through a geroscience framework, we have the opportunity to delay or even prevent AD onset. Rather than targeting downstream symptoms alone, emerging strategies seek to intervene earlier in the disease course by addressing the biological aging mechanisms that drive AD pathogenesis.

Future research should focus on integrated, multimodal interventions that combine lifestyle modification with pharmacological and biological therapies. Tailored approaches – based on genetic risk profiles (e.g., APOE status), comorbidities, and individual aging trajectories – may optimize clinical outcomes. To evaluate the long-term safety and effectiveness of innovative treatments like senolytics, epigenetic modulators, and stem cell-based therapies in older populations, extensive, longitudinal clinical trials are also required. Developments in biological age biomarkers, machine learning, and systems biology have the potential to improve risk assessment and therapy customization.

Информация об авторе

Information about the author

Халед А. Абдель-Шатер – доктор медицины, стоматологический факультет, Университет Мута.

E-mail: Kabdelsater@mutah.edu.jo; ORCID: 0000-0001-9357-4983

Khaled A. Abdel-Sater – MD, Faculty of Dentistry, Mutah University. E-mail: Kabdelsater@mutah.edu.jo; ORCID: 0000-0001-9357-4983

Поступила в редакцию: 20.07.2025

Поступила после рецензирования: 04.08.2025

Принята к публикации: 14.08.2025

Received: 20.07.2025

Revised: 04.08.2025

Accepted: 14.08.2025

Список исп. литературыСкрыть список1. Scheltens P, De Strooper B, Kivipelto M et al. Alzheimer's disease. Lancet 2021;397(10284):1577-90. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32205-4

2. Bellenguez C, Küçükali F, Jansen IE et al. New insights into the genetic etiology of Alzheimer's disease and related dementias. Nat Genet 2022;54(4):412-36. DOI: 10.1038/s41588-022-01024-z

3. Lopez-Lee C, Torres ERS, Carling G, Gan L. Mechanisms of sex differences in Alzheimer's disease. Neuron 2024;112(8):1208-21. DOI: 10.1016/j.Neuron.2024.01.024

4. Jiang Q, Liu J, Huang S et al. Antiageing strategy for neurodegenerative diseases: from mechanisms to clinical advances. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2025;(10):76. DOI: 10.1038/s41392-025-02145-7

5. Zhang XX, Tian Y, Wang ZT et al. The Epidemiology of Alzheimer's Disease Modifiable Risk Factors and Prevention. J Prev Alzheimers Dis 2021;8(3):313-21. DOI: 10.14283/jpad.2021.15

6. Sehar U, Rawat P, Reddy AP et al. Amyloid Beta in Aging and Alzheimer's Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2022;23(21):12924-7. DOI: 10.3390/ijms232112924

7. Kelliny S, Zhou XF, Bobrovskaya L. Alzheimer's Disease and Frontotemporal Dementia: A Review of Pathophysiology and Therapeutic Approaches. J Neurosci Res 2025;103(5):e70046-e70050. DOI: 10.1002/jnr.70046

8. Liu RM. Aging, Cellular Senescence, and Alzheimer's Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2022;23(4):1989-92. DOI: 10.3390/ijms23041989

9. Yoo HJ, Kwon MS. Aged Microglia in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Microglia Lifespan and Culture Methods. Front Aging Neurosci 2022;(13):766267. DOI: 10.3389/fnagi.2021.766267

10. Ana B. Aged-Related Changes in Microglia and Neurodegenerative Diseases: Exploring the Connection. Biomedicines 2024;12(8):1737-41. DOI: 10.3390/biomedicines12081737

11. Heavener KS, Bradshaw EM. The aging immune system in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases. Semin Immunopathol 2022;44(5):649-57. DOI: 10.1007/s00281-022-00944-6

12. Picca A, Ferri E, Calvani R et al. Age-Associated Glia Remodeling and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Neurodegeneration: Antioxidant Supplementation as a Possible Intervention. Nutrients 2022;14(12):2406-10. DOI: 10.3390/nu14122406

13. Ajoolabady A, Lindholm D, Ren J, Pratico D. ER stress and UPR in Alzheimer's disease: mechanisms, pathogenesis, treatments. Cell Death Dis 2022;13(8):706. DOI: 10.1038/s41419-022-05153-5

14. Kumari S, Dhapola R, Reddy DH. Apoptosis in Alzheimer's disease: insight into the signaling pathways and therapeutic avenues. Apoptosis 2023;28(7-8):943-57. DOI: 10.1007/s10495-023-01848-y

15. Liu Y, Xu C, Gu R et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in diseases. MedComm 2024;5(9):e701. DOI: 10.1002/mco2.701

16. Liu CC, Zhao J, Fu Y et al. Peripheral apoE4 enhances Alzheimer's pathology and impairs cognition by compromising cerebrovascular function. Nat Neurosci 2022;25(8):1020-33. DOI: 10.1038/s41593-022-01127-0

17. Tai LM, Ghura S, Koster KP et al. APOE-modulated Aβ-induced neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's disease: current landscape, novel data, and future perspective. J Neurochem 2015;133(4):465-88. DOI: 10.1111/jnc.13072

18. Ibrahim AM, Chauhan L, Bhardwaj A et al. Brain-Derived Neurotropic Factor in Neurodegenerative Disorders. Biomedicines 2022;10(5):1143. DOI: 10.3390/biomedicines10051143

19. Koya PC, Kolla SC, Madala V, Sayana SB. Potential of Nerve Growth Factor (NGF)- and Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF)-Targeted Gene Therapy for Alzheimer's Disease: A Narrative Review. Cureus 2025;17(6):e85814. DOI: 10.7759/cureus.85814

20. Verma M, Lizama BN, Chu CT. Excitotoxicity, calcium and mitochondria: a triad in synaptic neurodegeneration. Transl Neurodegener 2022;11(1):3. DOI: 10.1186/s40035-021-00278-7

21. Mizoguchi Y, Yao H, Imamura Y et al. Lower brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels are associated with age-related memory impairment in community-dwelling older adults: the Sefuri study. Sci Rep 2020;10(1):16442. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-020-73576-1

22. Sun S, Ma S, Cai Y et al. A single-cell transcriptomic atlas of exercise-induced anti-inflammatory and geroprotective effects across the body [published correction appears in Innovation (Camb). 2025; 6(2):100806. DOI: 10.1016/j.xinn.2025.100806.]. Innovation (Camb) 2023;4(1):100380. DOI: 10.1016/j.xinn.2023.100380

23. Kępka A, Ochocińska A, Borzym-Kluczyk M et al. Healthy Food Pyramid as Well as Physical and Mental Activity in the Prevention of Alzheimer's Disease. Nutrients 2022;14(8):1534. DOI: 10.3390/nu 14081534

24. Khalil MH. The BDNF-Interactive Model for Sustainable Hippocampal Neurogenesis in Humans: Synergistic Effects of Environmentally-Mediated Physical Activity, Cognitive Stimulation, and Mindfulness. Int J Mol Sci 2024;25(23):12924. DOI: 10.3390/ijms252312924

25. Barad Z, Augusto J, Kelly ÁM. Exercise-induced modulation of neuroinflammation in ageing. J Physiol 2023;601(11):2069-83. DOI: 10.1113/JP282894

26. Abraham MJ, El Sherbini A, El-Diasty M et al. Restoring Epigenetic Reprogramming with Diet and Exercise to Improve Health-Related Metabolic Diseases. Biomolecules 2023;13(2):318. DOI: 10.3390/biom 13020318

27. Sawda C, Moussa C, Turner RS. Resveratrol for Alzheimer's disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2017;1403(1):142-9. DOI: 10.1111/nyas.13431

28. Grant WB, Blake SM. Diet's Role in Modifying Risk of Alzheimer's Disease: History and Present Understanding. J Alzheimers Dis 2023;96(4):1353-82. DOI: 10.3233/JAD-230418

29. Ali AM, Kunugi H. Royal Jelly as an Intelligent Anti-Aging Agent-A Focus on Cognitive Aging and Alzheimer's Disease: A Review. Antioxidants (Basel) 2020;9(10):937. DOI: 10.3390/antiox9100937

30. Smith AD, Refsum H. Homocysteine, B Vitamins, and Cognitive Impairment. Annu Rev Nutr 2016;(36):211-39. DOI: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-071715-050947

31. Liu S, Gao J, Zhu M et al. Gut Microbiota and Dysbiosis in Alzheimer's Disease: Implications for Pathogenesis and Treatment. Mol Neurobiol 2020;57(12):5026-43. DOI: 10.1007/s12035-020-02073-3

32. Wiciński M, Erdmann J, Nowacka A et al. Natural Phytochemicals as SIRT Activators-Focus on Potential Biochemical Mechanisms. Nutrients 2023;15(16):3578. DOI: 10.3390/nu15163578

33. Mattson MP, Moehl K, Ghena N et al. Intermittent metabolic switching, neuroplasticity and brain health [published correction appears in Nat Rev Neurosci. 2020 Aug;21(8):445. DOI: 10.1038/s41583-020-0342-y.]. Nat Rev Neurosci 2018;19(2):63-80. DOI: 10.1038/nrn.2017.156

34. Yang Y, Zhang L. The effects of caloric restriction and its mimetics in Alzheimer's disease through autophagy pathways. Food Funct 2020;11(2):1211-24. DOI: 10.1039/c9fo02611h

35. Park S, Zhang T, Wu X, Yi Qiu J. Ketone production by ketogenic diet and by intermittent fasting has different effects on the gut microbiota and disease progression in an Alzheimer's disease rat model. J Clin Biochem Nutr 2020;67(2):188-98. DOI: 10.3164/jcbn.19-87

36. Trisal A, Singh AK. Clinical Insights on Caloric Restriction Mimetics for Mitigating Brain Aging and Related Neurodegeneration. Cell Mol Neurobiol 2024;44(1):67-70. DOI: 10.1007/s10571-024-01493-2

37. Nowell J, Blunt E, Gupta D, Edison P. Antidiabetic agents as a novel treatment for Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease. Ageing Res Rev 2023;(89):101979. DOI: 10.1016/j.arr.2023.101979

38. Satarker S, Wilson J, Kolathur KK et al. Spermidine as an epigenetic regulator of autophagy in neurodegenerative disorders. Eur J Pharmacol 2024;(979):176823. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2024.176823

39. Abdul-Rahman T, Awuah WA, Mikhailova T et al. Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and epigenetic potential of curcumin in Alzheimer's disease. Biofactors 2024;50(4):693-708. DOI: 10.1002/biof.2039

40. Fan L, Zhang Z. Therapeutic potential of curcumin on the cognitive decline in animal models of Alzheimer's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 2024;397(7):4499-509. DOI: 10.1007/s00210-024-02946-7

41. Alsaleem MA, Al-Kuraishy HM, Al-Gareeb AI et al. Molecular Signaling Pathways of Quercetin in Alzheimer's Disease: A Promising Arena. Cell Mol Neurobiol 2024;45(1):8. DOI: 10.1007/s10571-024-01526-w